HUNTSVILLE, Ala. — The Huntsville-Madison County Public Library has introduced a new system of library cards for children that restricts access to certain materials, a move aligned with recent Alabama state guidelines aimed at limiting exposure to what lawmakers consider “inappropriate” content. The tiered card system, which categorizes access into three levels based on age and parental preferences, has ignited controversy in a state already at the center of the national debate over library censorship.

Under the new system, children with a Level 1 card can only check out books from the juvenile section, while Level 2 allows access to the young adult section. A Level 3 card, issued with parental permission, grants full access to the library’s materials, including digital content and adult books.

While supporters of these changes argue that the policies are necessary to protect children from “sexually explicit” materials, critics argue that the restrictions unfairly target harmless and inclusive content, especially books centered on LGBTQ+ themes. The national organization Moms for Liberty, which has chapters in Madison and Baldwin counties, has been a vocal advocate for limiting access to books that they claim promote “gender ideology” or contain what they describe as “inappropriate” content for children.

This push for restrictions comes on the heels of Alabama’s broader legislative efforts to regulate the materials in public libraries. In 2023, the Alabama Public Library Service (APLS) issued guidance encouraging libraries to avoid purchasing books deemed to have “sexual content” for minors. The guidelines, while vague, have led to a wave of local measures restricting access to books that feature LGBTQ+ characters or themes, even when these books contain no graphic or sexual content.

Opponents of these laws, including advocacy groups such as Read Freely Alabama and the American Library Association (ALA), argue that these policies represent a form of censorship targeting vulnerable populations.

Many of the books that have come under scrutiny in Alabama, such as All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson and Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe, have been lauded for their candid portrayal of queer experiences. Supporters of these works argue that they are critical for creating inclusive spaces where young readers can see themselves reflected, particularly in conservative areas where LGBTQ+ visibility remains limited. However, under Alabama’s increasingly stringent guidelines, even these works—which contain little to no graphic content—are being labeled as inappropriate for younger readers.

The impact of these policies is being felt beyond Huntsville. Across Alabama, small and rural libraries that receive state funding are now under pressure to implement similar restrictions or risk losing financial support from the state. Critics point out that the focus on “protecting children” from so-called harmful content disproportionately affects marginalized communities by silencing diverse voices.

As Alabama moves further down the path of restricting library access, the debate is far from settled. Advocates for intellectual freedom continue to call for policies that empower parents to make decisions for their own children without imposing blanket restrictions that impact entire communities. For many, the recent changes in Huntsville are just one step in a larger battle over who controls the narrative in Alabama’s public spaces.

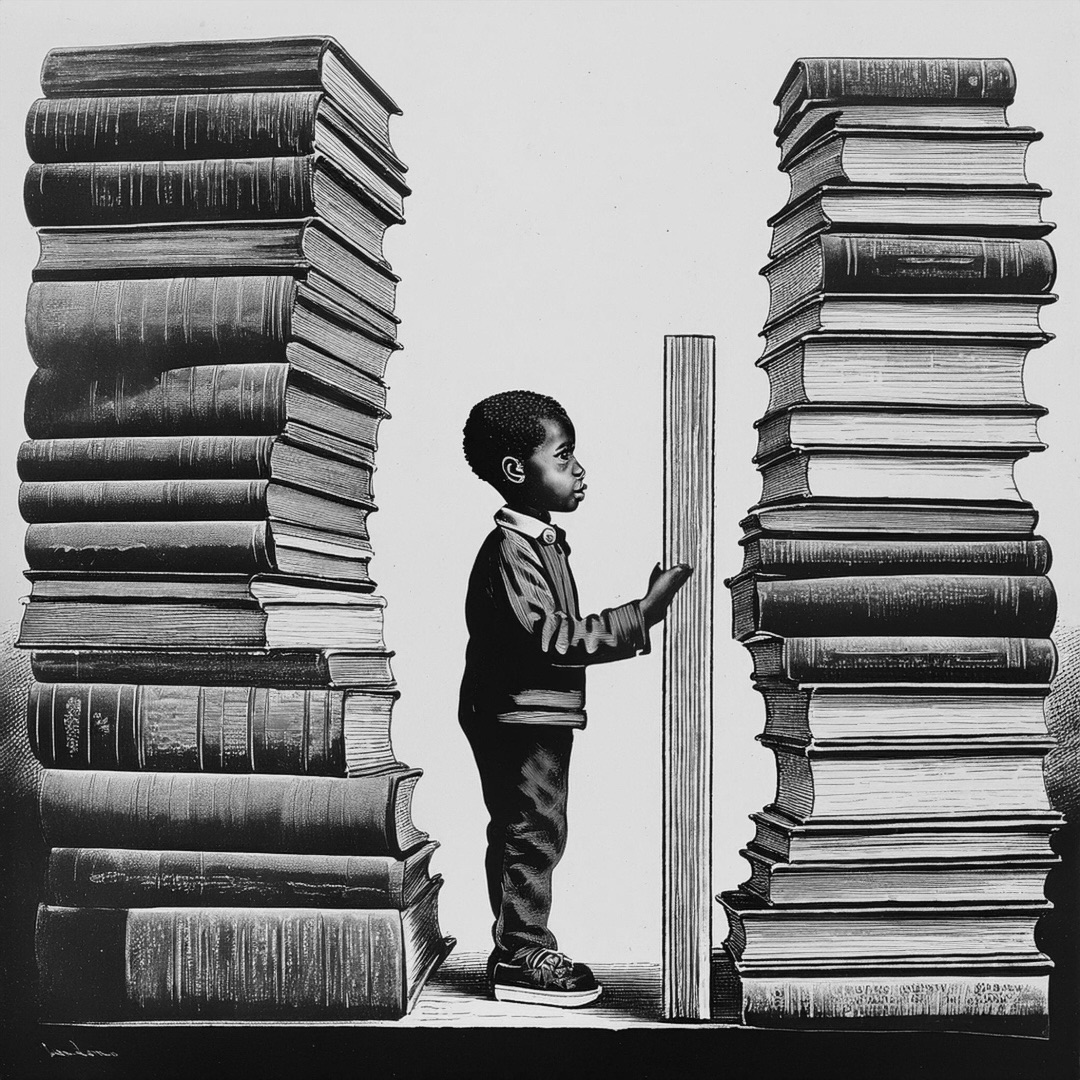

For now, Alabama’s youngest readers may find that their access to books telling stories of inclusion, acceptance, and diversity is increasingly limited—not by their own choices or needs, but by the decisions of legislators and advocacy groups determined to control what children can read.