When Happy Hooligan debuted in 1899, readers met a bumbling, kind-hearted tramp who quickly became one of the earliest comic strip icons. Created by Frederick Burr Opper, Happy Hooligan chronicled the well-meaning but constantly unlucky exploits of its titular character—a man who could never catch a break, no matter how hard he tried. Wearing a tin can for a hat and an eternal smile, Happy was the embodiment of optimism in the face of failure.

Frederick Burr Opper, born in Ohio in 1857, had a long career as a political cartoonist before transitioning into the relatively new medium of newspaper comics.

By the time he created Happy Hooligan, Opper had already honed his talent for visual storytelling and slapstick humor. His earlier work in magazines like Puck and Harper’s Weekly showcased his keen sense of caricature and satire, but it was in Happy Hooligan that his light-hearted, chaotic style fully blossomed.

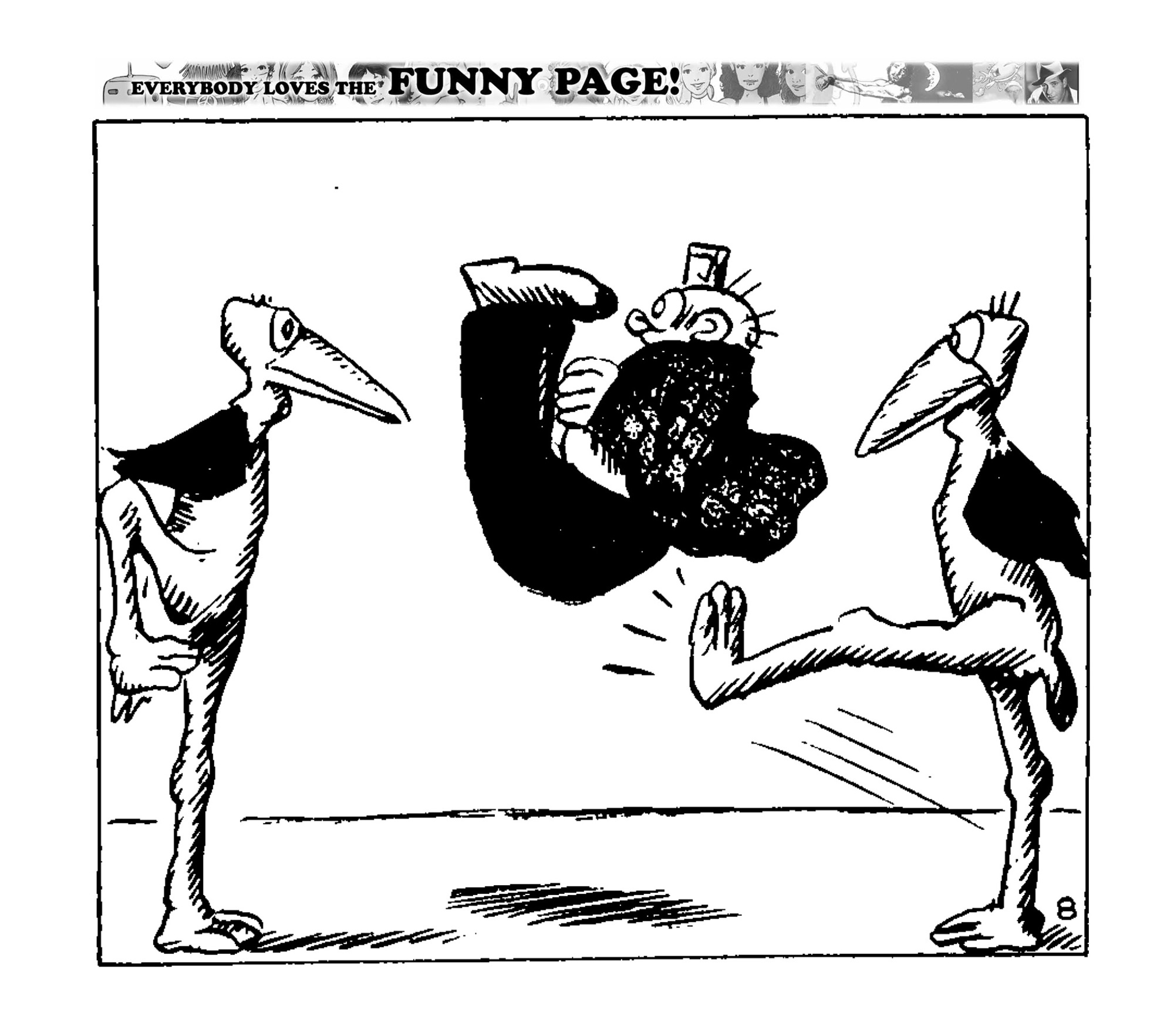

In each strip, Happy’s good intentions always led to disaster—whether it was accidentally destroying property or being wrongly jailed—but he never lost his upbeat attitude. The charm of the strip lay in Happy’s resilience.

He wasn’t trying to scheme his way to success like other comic characters of the era; instead, he was endlessly well-meaning, if perpetually unlucky. His tin can hat became a symbol of his poverty but also his humorous resilience, embodying the scrappiness that defined him.

Opper’s illustrations were lively and unrefined, complementing the haphazard energy of Happy’s adventures. The loose, hurried lines of his drawings matched the slapstick nature of the strip, making the humor feel spontaneous.

Happy was often accompanied by his more refined brother, Montmorency, whose presence highlighted the comic tension between class and circumstance, but Happy’s optimism always overshadowed his bad luck.

Happy Hooligan was hugely popular during its run and reflected the struggles of the working-class urban audience. His mishaps resonated with readers, particularly immigrants and laborers, who saw in Happy their own day-to-day challenges and small victories.

Happy’s lack of sophistication and his constant failures were not so much a defeat as they were an invitation to keep trying. In a sense, the comic strip was a reflection of the American dream’s most resilient side—the belief that, eventually, effort would pay off, even if the journey was full of falls.

Opper retired Happy Hooligan in 1932 after 33 years of laughs and misadventures. By then, the comic strip landscape had evolved, but Happy Hooligan left its mark, pioneering slapstick humor in the medium.

Frederick Burr Opper’s work remains a delightful example of how comics could capture everyday life with humor and heart, proving that sometimes, the real hero is simply the one who keeps getting back up.